The napkin sketch has held a unique place in the design process in many fields, architecture included. Napkin sketches from famous designers have been studied, emulated, placed in museums, and even auctioned off. Some believe these sketches are markers of spontaneous design genius and have driven a project’s building form or style.

And while I may admire a napkin sketch, I don’t think it helps drive regenerative design thinking.

Now, before the pitchforks come out, I’m not advocating that designers stop sketching. What I am championing for is an evolution of this time-honored process into something that is deliberate, not spontaneous; considerate, not parochial; broader than the perceived project boundaries, not confined to one physical site; and most importantly, delayed until the following four steps have been executed.

[Related: Data-Driven Building Design that Gives More Than It Takes]

1. Gain a Deep Understanding of Climate and Place

This wisdom is what Regenesis, pioneers in regenerative design, calls being “grounded in place,” and a project team could spend months—if not years—striving to understand the true purpose and identity of a given project site. Given that design teams are under ever-increasing pressure to produce design ideas, this can be the most challenging step of all—yet it’s by far the most important. Using weather files, parametric analytic software and GIS maps, design teams can create automated reports to help inform a design process that’s under a time constraint.

Understanding nested ecological systems can help a team prioritize various strategies that can help them achieve regenerative metrics for a project. For example, a project with a high water stress risk value may be at a greater risk given future climate change models for temperature increase and precipitation decrease.

This knowledge would encourage a project team to emulate natural system metrics from a nearby ecological baseline all while planning for future impacts to the system. It’s more difficult to rethink site parameters, building program spaces and on-site capture, infiltration, and reuse if a building is sketched out and the client has approved the concept.

2. Establish an Ecological Reference Site

The Industrial Revolution has significantly eroded the relationship between the built environment as a part of nature. However, projects that are designed to emulate a natural site with natural ecological systems can begin to identify with natural interconnected systems and their associated performance metrics. Characteristics of an ecological reference site include:

- A location within the same climate zone as the project site.

- The same ecoregion designation as the project site at the most detailed level. (In the U.S., this would be Ecoregion IV as defined by the Environmental Protection Agency.)

- Be as “pristine” and impacted as little as possible by human development. However, biologists and environmental scientists who have worked on remote sites throughout the entire globe tell me that they are still searching for a truly “pristine” site given the reach of human impact. A designer’s job is to try to identify a site that comes close. Simply referencing a local stormwater code isn’t going to take us into uncharted regenerative territory and allows us to emulate natural water cycle performance metrics.

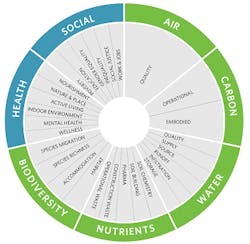

An ecological reference site can be emulated for performance metrics such as water runoff, water infiltration, evapotranspiration, biodiversity, species thriving, air quality, water quality, soil pH levels, soil nutrient levels, soil building and soil/vegetation carbon sequestration capacity.

To go deeper, design teams can discover design strategies in and around this ecological base line site to support the achievement of these natural metrics through what the Biomimicry Guild calls the “Genius of Place.” Emulating organism and system functions even through mechanical means within the project can achieve these natural metrics. Projects may not be able to achieve all targets, but the gap between our project’s performance and the performance of natural systems is now benchmarked.

[Related: Inside San Francisco Airport’s Triple Zero Plan]

3. Engage the Community as an Active and Ongoing Stakeholder

Ecological systems are directly impacted by social systems and should co-evolve together. Even though humans are, in fact, a part of nature, the divide and characteristics between these two systems is now so vast that they must work separately, but in symbiosis. A need is also growing for design teams to address social issues such as equity, environmental justice and health on projects. Designers are ethically responsible to improve the human condition and we must address these social systems regardless of the project type and location.

For example, project teams that look beyond the immediate social system into a greater nested whole may find that the energy used on site is being supplied by a power plant with high emission intensities miles away. This plant is likely creating air quality issues for nearby socially vulnerable communities whose residents tend to have higher rates of asthma and heart disease.

The project, then, directly contributes to a cycle of poor health, economics and ecology in that community. By engaging community stakeholders, you are offering them the opportunity to have a say in decisions that impact their health, their environment and their wallets.

4. Set a Vision and Goals with Regenerative Metrics in Place

A vision is the ability to think about and plan for the future with imagination and wisdom. Without a vision statement or project identity, without wisdom of the place and associated goals or metrics for social and ecological systems, a truly informed and effective design solution can’t exist. Design teams should review data from the nested social and ecological systems with client and community stakeholders to set specific metrics for the project.

Any scribbles produced before these four steps still capture imagination and wisdom, but they’re vestiges from past projects with their own unique realities. We have a monumental task ahead of us to change the process.

If the design profession believes that it can solve the pending impacts of climate change and ecosystem collapse with the same approach and ideas from the past, we’re fooling ourselves. Let’s all be bold and embrace new design processes that lead us in the direction of our future survival.

About the Author:

Colin Rohlfing is the sustainable design leader for HDR.

Read next: 6 Ideas to Create Net-Positive, Ultra-Green Museums