How an Iconic Brutalist Building Became One of the Most Sustainable Hotels in the U.S.

It’s been said the most sustainable buildings are the ones that already exist. Indeed, adaptive reuse and historic renovation projects have the benefit of preserving existing building materials and the embodied carbon within them, diverting construction waste from landfills and utilizing less energy compared to new construction projects.

However, transforming a 50-year-old office building into one of the most sustainable hotels in the country is another story altogether. But that’s exactly what architect and developer Bruce Redman Becker of Becker + Becker set out to do when he purchased the historic Pirelli Tire Building in New Haven, Connecticut, in 2020.

Listed on the State and National Register of Historic Places, the icon of Brutalist architecture is now getting a second life as the Hotel Marcel (opening in April 2022), the country’s first Passive House certified and first net zero energy hotel, and one of only about a dozen LEED Platinum-certified hotels in the U.S.

The hotel will feature 165 guest rooms and suites, full-service new American restaurant and bar, a lounge and 7,000 square feet of meeting and event space with penthouse courtyard and galleries. More importantly, Hotel Marcel will be all-electric, generating 100% of its own electricity and energy for heat and hot water with a rooftop solar array and solar parking canopies.

The remodeled property will also include many cutting-edge technologies to modernize the building, including a Power over Ethernet (PoE) lighting system, renewable on-site energy generation, plus extensive upgrades to enhance interior temperature control and air quality. The building’s Energy Use Intensity (EUI) rating is projected to be 34 kBtu per square foot—80% less energy than the median EUI for hotels in the U.S.

“With the climate crisis and continued use of fossil fuels posing an existential threat to humanity, I felt an obligation to build a building that can serve as a model for environmental sustainability,” Becker said. “The question should not be why are we doing this, but why isn't everyone else?”

The property’s design is a collaboration between Becker + Becker, project architect, and New York City-based interior design and branding studio Dutch East Design, founded by visionaries Larah Moravek, Dieter Cartwright and William Oberlin. Dutch East Design was engaged to design Hotel Marcel’s visual identity and interior design.

“It is a rare opportunity to be offered such an iconic structure to reimagine into a hotel,” said Larah Moravek, co-founder of Dutch East Design. “We wanted to honor the distinct architecture and celebrate the building in all its glory. We took an intentional position to allow the interiors to be the soft underbelly of the Brutalist exoskeleton.”

A Storied History

The Pirelli Building, as it has become known, has a storied past. Armstrong Rubber Co. first initiated the building’s construction in 1966 with a proposal to develop a site at the intersection of Interstates 91 and 95 to then-mayor of New Haven, Richard C. Lee. While the company originally proposed a low-rise structure, Lee suggested an eight- to 10-story development instead.

In response, project architect Marcel Breuer designed a plan suspending the company’s administrative offices two stories above a two-story research and development space. The project was completed in 1970, featuring the distinctive negative space between the building’s two forms that gives the administrative tower portion the illusion of suspension. Enveloping the entire building are pre-cast concrete panels of varying scale and design that provide protection from the sun and give the facade striking physicality and depth.

[Related: Meet the Historic Building at the Center of Dallas’ West End Revival]

In 1988, Pirelli purchased Armstrong Rubber, selling the site soon after. It sat empty for decades with a large portion of the structure demolished at one point to make way for a parking lot. The abandoned building was reportedly criticized by preservation groups as “demolition by neglect” until Becker’s renovation of the property, which has drawn significant media attention celebrating its innovative and sustainable design.

Inviting Interiors

Upon arrival, guests are met by a palette of warm earth tones with a textural buildup of stone finishes, found in the custom wood reception desk, and eye-catching terra cotta in a Cle Tile feature wall, complemented by custom lighting designed by Dutch East.

An existing depressed floorplate on the North end was transformed into a sunken lounge that works as the lobby lounge as well as pre-function space should the pivot doors open up from the forum and function spaces, allowing hotel guests to meander and discover various seating vignettes. The furniture, carpets, area rugs and lighting are custom designed by Dutch East Design, deploying Bauhaus-inspired patterning throughout all the textiles.

The historic ceiling has been reinstated to respond to the interior layout, providing an open plane of intersecting ceiling tiles that accommodate the reimagined original architectural lighting system with new custom faceted acrylic lens panels.

Minimalist and inviting, most of the 165 guest rooms utilize concrete grey, caramel vinyl and walnut throughout, emphasized by pops of muted dark green and sienna and sculptural decorative lighting. Following the original floor plans of the office floor, the rooms achieve an openness through interlocking elements, with the closet connecting with the nightstand and headboard of the platform bed frame. On the opposing side of the room sits a sculptural cast concrete table, celebrating the concrete exterior of the building.

Guests who wander up to the ninth floor will find a James Turrell-like experience, serving as an event space with an interior courtyard and light wells created to add natural light. Boasting 15-foot-high ceilings, previously home to the building’s HVAC system, the space unveils the masterful and artistic truss system, the imprint of which is cast as a relief into the building’s exterior. Coming off the elevators, guests are welcomed by a feature screen leading to the large flexible event space beyond.

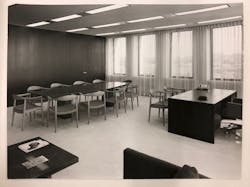

On the eighth floor live the hotel’s nine historic rooms and suites, highlighting the carefully restored and preserved wood paneled walls of what were once executive offices and conference rooms. Offsetting the rich color of the wood, Dutch East selected oak for the casegoods and a blend of light blues and warm grays in textiles throughout the space’s lounge area, kitchenette and bedroom.

Throughout the hotel, nods to Marcel Breuer’s pioneering work at the Bauhaus are intentional, from custom carpets with an over-scaled Bauhaus-inspired graphic found in the suites to the chevron patterns on the standard guest room carpeting. The Dutch East team also incorporated the angular geometry of the exterior window panels into the wood detailing on the interior, celebrating Breuer’s brutalist language in the guestroom corridor ceiling panels.

Hotel Marcel stands as a testament to the fact that historic buildings can not only be iconic, but also innovative in their approach to sustainable development.

Read next: Why Buildings That Battle Carbon Are Needed in the Fight Against Climate Change