By Steve Silicato

Each year, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry evaluate substances found in the workplace that are dangerous or potentially harmful to human health or the environment. And, with each review, the list seems to grow. For example, chemical fire extinguishers, fluorescent light tubes, high-intensity discharge lamps, and mercury thermostat switches are just a few of the items containing substances that are now regulated and must be properly managed and disposed of following proper procedures. But, what are the most common hazards that facility managers will probably encounter and be asked to remediate in a commercial building? Most likely, the hazards will include asbestos-containing materials, lead-based paint, and mold.

Asbestos and lead may be found in older buildings, installed at the time when asbestos was known as a "miracle fiber" and used extensively in factories, schools, hospitals, and thousands of commercial and residential buildings across the United States, and when lead was a key ingredient in nearly all paint being used on both the interior and exterior of buildings. Mold, on the other hand, has always been present in the environment and can be present in both old and new construction.

Take a look at these three hazards, find out how they should be identified and analyzed, and read about the steps for abatement and remediation.

Free of Asbestos?

The height of asbestos use was between 1930 and 1950, when it was commonly used in the production of insulation for mechanical and plumbing system components such as pipes, duct, boilers, and tanks. It was also used as an ingredient in acoustical insulation and for decorative purposes on ceilings and walls. As a fire-retardant insulation, it was used on structural beams and firewalls, and in fire doors. Until the late 1970s, there were no protocols for the demolition and removal of building asbestos. By 1986, President Ronald Reagan had signed the Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act to require regulations for the inspection of asbestos-containing materials and the appropriate response actions.

Removal of asbestos boiler insulation.

Although asbestos spray-on fireproofing and thermal systems insulation have been banned in building construction since the mid 1970s, owners and managers of commercial and industrial buildings constructed before 1981 must determine if asbestos is present in any building materials that will be disturbed or impacted prior to renovation or demolition. There are still plenty of asbestos materials remaining in buildings constructed before (and after) 1981. Most of the asbestos-containing materials being used in building products today are found in building products being imported from countries such as Canada and China.

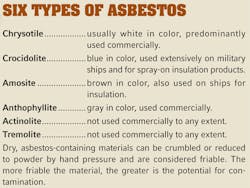

The only way to truly determine if building materials contain asbestos is through laboratory analysis with the aid of a special type of microscope. (See Six Types of Asbestos) For this reason, facility managers who suspect the presence of asbestos-containing material should enlist the aid of an environmental consultant to determine if the material is asbestos prior to conducting renovation or demolition. Once asbestos is confirmed in those building materials, the building owner or facility manager should find an environmental contractor with the proper licenses to properly remove and dispose of the materials. (See How to Find a Qualified Contractor)

There are five possible approaches to dealing with asbestos:

- Operations and maintenance (O&M) programs. The building operator establishes a complete O&M program for the purposes of cleaning up an unanticipated release, preventing future release of fibers, and monitoring and managing the condition of asbestos-containing material left in place.

- Patch and repair. This is an integral part of any O&M program because fiber release is controlled quickly and is less costly than total removal.

- Removal. This involves stripping out and disposing of the asbestos-containing material. The asbestos source is eliminated and future problems are prevented.

- Encapsulation. This involves the use of an EPA-registered sealant that is applied onto the asbestos-containing material to prevent fiber release.

- Enclosure. In this process, a barrier is constructed between the asbestos and the surrounding environment, thereby controlling exposure to fiber release; however, the asbestos source remains.

The environmental consultant, in agreement with the environmental contractor, will recommend the best approach to take in each circumstance. It is important to remember that poorly performed work can create a much greater exposure hazard than doing nothing at all.

In a typical asbestos-abatement project, caution signs and barrier tape are posted in accordance with Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA)/EPA requirements to demarcate and prevent people from entering the hazardous area unprotected. The contractor should use a minimum of two layers of 6-mil poly sheeting to seal off the area. Moveable objects should be removed; stationary objects should be pre-cleaned using HEPA-filtered vacuum equipment, then sealed with poly sheeting for protection.

Workers enter and exit the work area through an enclosed, three-stage decontamination system, which is an airlock system consisting of at least two curtained doorways approximately 6 feet apart. Change rooms, showers, and decontamination areas must be provided to prevent contaminated dust from being carried outside the work areas.

Lead: Highly Toxic Metal

Lead is a naturally occurring, bluish-gray, highly toxic metal found throughout the environment and created by human activities such as burning fossil fuel, mining, and manufacturing. It has many different uses, including use in the production of batteries, ammunition, metal products like solder and pipe, and devices to shield X-rays. Because of health concerns, lead from paints and ceramic products, caulking, and pipe solder has been dramatically reduced in recent years. Paint with a high concentration of lead can often be found in and around homes and businesses built before 1978. The primary sources of lead exposure to humans in the daily environment are deteriorating lead-based paint and lead-contaminated dust. (Lead paint in good condition is not a cause for concern unless it's loose, flaking, or forming dust.)

A close-up of lead-based paint.

Movement of lead from soil into groundwater will depend on the type of lead compound and the characteristics of the soil. To remediate potential contamination, facilities with outdoor gun ranges must deal with the lead left by bullet fragments. A patented pneumatic unit is available to segregate lead bullet fragments from soil, rocks, and debris, and prevent contamination.

Surficial lead abatement techniques can include:

- Chemical stripping. A solvent or caustic stripper is applied to the painted surface with a brush or sprayer. After an appropriate period of time, mechanical strippers, a HEPA-vacuum system, or pressurized water may be used to remove the chemical strippers and lead-based paint. This method minimizes airborne lead concentrations, reducing environmental risks and the need for costly enclosures.

- Abrasive blasting. A blast nozzle is attached to a brush-lined shroud, which is held against the lead-based coating to be removed. The abrasive and the debris are contained within the tool itself. While blasting, a built-in vacuum system carries the material to a collection bin. The abrasive can then be disposed of or cleaned and recycled. This method reduces lead exposure and minimizes needs for containment. Various types of abrasive blasting media include sand, sponge, baking soda, or even high-pressure water.

- Industrial vacuuming. Lead dust resulting from industrial or manufacturing processes can accumulate on surfaces and must be HEPA vacuumed and wiped from the surfaces. Wipe sampling is conducted to ensure that OSHA standards for cleanliness and acceptable lead levels have been met.

The environmental consultant should work with the abatement contractor to determine the most cost-effective method of lead abatement for a building, including those pursuing historic preservation.

Remediate Mold Immediately

The flurry of news reports and industry concern about the danger of indoor mold growth have been similar to the asbestos scares in the 1980s and the concern about lead poisoning soon after, although to a lesser extent. Yet, with all of the media attention, there still exists confusion as to what constitutes mold. Molds and mildew are simple, microscopic fungi that grow on surfaces where there is an organic food source. Many of the construction materials used, such as wood, carpet, glue, and cellulose-based objects like ceiling panels and drywall, are hosts for indoor mold growth.

Negative air machines with HEPA filters are used to filter the air during mold removal.

Human response to mold exposure varies widely. More than 100,000 species of mold exist, but only a small number are suspected of having the potential to negatively affect human health if touched, inhaled, or ingested. Health experts agree that mold should not be allowed to continue to grow and proliferate on indoor surfaces, and should be remediated immediately upon visual identification.

Complaints about mold contamination increased dramatically in the 1980s, when construction techniques emphasized airtight buildings to promote energy efficiency. The problem was that buildings were not allowed to breathe, which is necessary to keep moisture in the buildings from reaching a level where mold can grow. The new discipline called "building science" has greatly evolved to incorporate environmental control systems, construction methods, and building materials that create a healthier, more sustainable, and more energy-efficient building environment. This has led to new approaches to stop moisture intrusion and ventilate structures.

Since water or moisture intrusion is one of the key elements that support indoor mold growth, the first step is to hire a qualified, experienced indoor air quality consultant to perform a moisture/mold assessment. This will help to identify the root cause of the mold growth and determine a repair or corrective action to mitigate the root cause. The next step is for the facility manager to hire a qualified, experienced mold remediation contractor to work with the consultant to develop the appropriate scope of work and means/methods for remediating the indoor mold growth.

Several accepted standards of care exist that describe recommendations for facility and building managers to deal with indoor mold issues: "Mold Remediation in Schools and Commercial Buildings" from the EPA, "Assessment & Remediation of Fungi in Indoor Environments" from the New York City Department of Health, and "Bioaerosols: Assessment & Control" from the American Conference of Government Industrial Hygienists, and the Institute of Inspection, Cleaning and Restoration Certification (IICRC) S-520.

It is recommended that building owners and facility managers educate themselves with these standards of care and guidelines, and use contractors who are well versed in them as well.

Many of these industry guidelines recommend the use of engineering controls similar to what is used on asbestos abatement projects for certain types of mold remediation projects. There are many similarities between asbestos abatement and mold remediation, but there are also some differences.

How can you be certain that mold remediation/clean-up has been successful? EPA guidelines state that the moisture problem must be fixed, mold removal should be complete, quantity and types of mold in the building should be similar to those found outside, the site should be revisited to check for signs of water damage or mold growth, and people should be able to reoccupy the space without health complaints.

Mold remediation is still an evolving industry. There is no current federal legislation for mold remediation like there is for asbestos abatement. Currently, there are only two states that require mold remediation contractors and testing firms to possess licenses. There are more states with legislation pending and/or to be introduced. This opens the door for unqualified and unscrupulous companies to enter the arena. With the liability issues that come along with mold infestation, the selection process of the mold remediation contractor should be just as important as the selection of an attorney, a medical expert, an indoor air quality consultant, a mechanical systems/energy consultant, or a building envelope expert. The decision can be that critical.

Steve Silicato is vice president at MARCOR Remediation Inc., headquartered in Hunt Valley, MD. He can be reached at (877) 6-MARCOR or at ([email protected]).