When Should the Owner Initiate Rooftop Action?

With building owners and managers so busy, roofs are unlikely to get much attention until they become troublesome. Our goal in this column is to focus on some proactive steps beyond the routine bi-annual inspections.

The first of these actions involves nothing more than taking a good hard look at who is currently accessing your roofs. Most low-slope roofs are used as equipment platforms. This means people have to get up there to perform maintenance, change filters, install new equipment, and make repairs. Unfortunately, roofs are also used as a place to take a smoke break when access is easier than wending ones way to a ground floor exit or break area. During the World Series, March Madness and other sport playoffs, roofs sprout radio and TV antennae as well.

People problems

Access to the roof, per se, is not evil, but the associated traffic patterns and work habits are rarely to the roof's benefit. A typical scenario is one where a worker accesses the roof through a roof scuttle or penthouse door. Naturally the worker is carrying tools or equipment. Just setting the toolbox on the roof membrane while climbing through the roof hatch is likely to do puncture damage. Next, the mechanic heads for the area where he needs to be. That will always be the most direct route, regardless of any aesthetically pleasing rectangular walkway previously installed. Arriving at the work point, the toolbox is again set down in order to remove a sheet-metal access door. Somehow, human nature being what it is, the door will be stood leaning against the HVAC unit, and gravity being what it is, one corner will dig (gouge) into the roof membrane.

Consequences of these random acts

The first issue is one of punctures. Many roof membranes are astonishingly thin. Many single-ply membranes are only 0.045 inches thick. Modified bitumens are somewhat thicker, with the cap sheet about 0.160" and the base another 0.1". Even a 4-ply built-up roof is only about 1/8" to 1/4" thick, so all membranes are pretty thin. Even a Galvalume-coated steel roof is usually only 24 or 26 gauge (0.021 to 0.026"). It doesn't take much to dent or puncture these materials. Roofs membranes are especially vulnerable when they have blisters or ridges.

Enhancing puncture resistance can take many forms. For single-ply membranes, increasing membrane thickness at the design stage can be very cost effective, as the labor for installing a 90 mil (0.090") sheet is hardly more than for a 45 mil sheet. Using a polyester-reinforced SBS cap sheet as a walkway on BUR and Mod Bit systems has proven itself many times over. However, the walkway needs to be put directly on the membrane, not over an installed gravel layer.

Wood "duck-boards" installed over sleepers provides a very high impact and traffic resistant surface. However, being out in the weather the wood itself, (even when treated), has a short life. Moreover, as the nails back out or the walkway disintegrates, the walkway itself becomes a hazard.

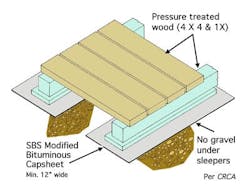

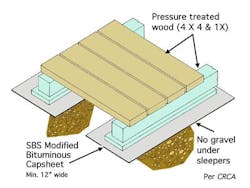

On bituminous roofing systems, one way to enhance "sleeper" or dunnage protection is to first install a polyester reinforced SBS modified cap sheet. For new design, this is installed directly over the bituminous membrane, fully adhered with hot asphalt or cold adhesive, torched in place, or using one of the newer self adhering materials. If a flood coat and gravel are used as surfacing, this goes around the cap sheet/walkway, not onto it. Figure 1 illustrates such an application. (Drawing courtesy of the Canadian Roofing Contractors Association). Note that this method would work to support pipes and rooftop equipment as well as duckboards.

In a retro situation, it is necessary to remove the flood coat and gravel, generally by using a 'spud-bar', and of necessity in cool weather when the bitumen is brittle and easy to shatter. If the membrane has been damaged by this step, patch it with another piece of Modified Sheet or BUR ply sheet prior to the application of the walkway sheet.

PageBreakFor unsurfaced single ply membranes, there are some simple techniques for enhancing puncture protection. One choice is to use a pad of non-woven fabric, (fleece), followed by a concrete paver. If the roof were ballasted, the ballast would be swept off the area to be protected. Since the pavers are generally about 2" thick, it is necessary to leave a gap between them so they do not hinder drainage.

Another choice is to use a specially designed walkway that is compatible with the membrane system. For example, on a weldable thermoplastic membrane (PVC, TPO, KEE, or copolymer), most manufacturers offer protective pads. These pads are generally thicker than the membrane itself. They are embossed for slip protection and sometimes colored brightly to indicate where the walkway is. While some suppliers recommend that the pad be completely sealed to the membrane, this is harder to do than one might think. In addition, if the pad shrinks or curls, it can degrade the membrane's performance. Perhaps a better choice is to use a pad with factory welded bonding tabs. The walkway is laid loose, and just welded at the tabs. This facilitates drainage of water that gets under the walkway, and somewhat isolates the pad from the membrane.

Vulcanized system walkways

In addition to the paver/fleece method mentioned above, many EPDM suppliers also offer elastomeric walkpads. Many of the early versions consisted of recycled rubber, and unfortunately they tended to disintegrate over time. Newer versions use EPDM on the weather side for superior weather resistance. In some, a thick punched rubber underlay is used. This engages the feet on the underside of the pavers and locks them together for better wind resistance. They are also suitable for creating a patio or break area on a roof.

Protecting against Chemical and Heat Degradation

There are other problems taking place on some roofs that are not directly people related. These would include fumes, particulates or contaminants exhausted onto the roof surface. While EPDM has outstanding weather resistance, it is adversely affected by oils, greases and animal fats. The product will pucker, swell and sometimes turn to jelly. If an owner discovers such a case and the emission cannot be eliminated, the best solution is to select a material that can resist such attack, and to reroof this area with this alternative material. Neoprene and Polyepichlorohydrin have worked. The areas beyond the influence of the chemical can remain EPDM.

Aliphatic solvents, i.e., paint thinner, and aromatic solvents (toluene, xylene) are tough on many membranes. If you know whose membrane is on the roof, consult with the membrane manufacturer for recommendations. Less satisfactory solutions may be to install a sacrificial membrane that is spot-attached to the waterproofing membrane, and replace it every six months or so. Another is to form a giant sandbox on the roof to trap the offending chemical, and replace the kitty-litter periodically.

Particulates such as food grain, paper or cardboard chips and the like are vexing problems. They expand when wet, and shrivel as they dry. This tends to claw at the membrane, pulling laps open and inducing stress cracks. They can assist the germination of airborne seeds and provide a medium for the growth of foliage. Owners that have such residues accumulating on the roof need to schedule regular maintenance. Some owners engage roofing contractors to shovel the mess off the roof, having observed that in-house personnel damage the roof and don't know how to fix the damage. Let the roofer do it, and at least the obvious punctures from shovels, carts, etc will get repaired immediately.

As Pogo once said, we have found the [roof's] enemy, and it is us.