With school districts across the country outgrowing their aging or too-small educational facilities, school boards and officials are faced with a multifaceted dilemma: renovate or build new? Design from scratch, or buy a design off the shelf? What will save money, and what will benefit the students? The questions may seem overwhelming, but the answer may rest in a simple, tested solution - prototype design for educational facilities.

While it's not a new concept, prototype schools deserve a second look in today's economic and environmental situation with their ability to save time, cut costs, and more quickly implement sustainable features across entire school districts.

Quick Tips for Prototype Design

-

Ask the community before you plan to implement prototype school design.

-

Make sure you get the electronic drawings/rights to the architectural drawings so you don't end up paying for them more than once.

-

Document any changes made to the design during construction so the next building project is up to date.

-

Customize the school for identity by using different paint colors and finishes inside, and different bricks, entrances, and window configurations outside.

-

Evaluate the shelf life of your prototype before planning more.

-

Don't expect the process to go perfectly; every construction project has its problems.

-

Ask teachers/students what they think of the facility before tweaking the design for the next building.

From conception, prototype designs are meant to be repeated at several sites; a prototype school design must meet the generic requirements of typical educational programs and be able to adapt to different sites without substantial modifications. " 'Prototype' is a term we use to define the reuse of a building type or building design," says Tom Hughes, principal at Raleigh, NC-based SFL+a Architects. "In order to keep up with growth, most districts don't have the time to design each building uniquely every time. Certainly, you'd love to design every school uniquely, and yet the economy, the time - it all weighs in. And, so, you work with the sensibility of a prototype."

Hughes cites Union County, NC, as an example of how growth is pressing officials to build faster to keep up with the demand for room. Listed by the U.S. Census Bureau as one of the top 10 growing counties in the nation, Union County's public schools are forced to make tough decisions - the growth of the student body doesn't necessarily mean a fatter budget. Wake County in North Carolina is also growing quickly and will need 50 new schools over the next 10 years. "These communities are faced with a real challenge to put up buildings as economically as they can, and yet they still have to be good schools," says Hughes.

Why Choose Prototype Design?

Because, in theory, prototype schools only have to be designed once, the timeline for the second school built with that design is narrowed from 10 to 14 months down to somewhere around 4 months. This expediency in delivery allows needs to be met much faster than with a typical design and construction process. "You're looking at a substantial amount of time invested in designing that first school, and yet you can turn around and flip the prototype with a shorter turnaround because, basically, the building design is the same," says Hughes.

If time is money, the shortened timeline will clearly result in savings for the district. Also, knowing how much it costs to build and operate the prototype will make it easier to benchmark costs across all your school buildings of the same design. "Costs can be accurately predicted from year to year," says Jan Taniguchi, principal at STR Partners LLC, Chicago. Colby Lewis, management partner, also at STR, adds, "There's reduced risk. There's cost predictability. [The prototype] has been built by contractors that have an established record of costs for that building; since they're comfortable with it, they're able to hone their prices, too."

After the first prototype school is built, a construction schedule can be nailed down and revised for the next project. Using the same contractors and having an experienced crew will also speed the process. "These guys have built it before," says Lewis. "They know how long it takes."

Jim French, senior principal at Overland Park, KS-based DLR Group, also sees reduced risk in the familiarity that communities can have with the prototype if there is a standing example, even if it's in another school district. "I think one of the reasons that prototypes are popular is because people know what they're getting," says French. "There are no secrets. They like to go see it, touch it, feel it, and know it."

A real-life example of cost savings is found in Florida's Miami-Dade County, where the prototype process saved the district approximately $9 million in planning costs across 12 schools. The district also standardized air filters, lamps, and flooring so the FM teams could buy supplies and products in bulk to save money.

The Prototype Process

Before deals are made with any architects, make sure prototype design schools are really the best choice for your district. "The district needs to find out: Does the community want prototypes?" says French. "When they drive around their community and see a building, will they say, ‘That's one of our elementary schools, and we really identify with that,' or do they want some autonomy among their schools?" Offer forums or surveys to determine the interest of the community, and make sure the school board is presented with accurate, thorough information. French adds that, "nine times out of 10, they want as cost-effective buildings as possible, and that's why prototypes have gotten so popular."

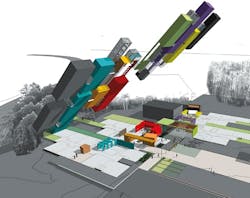

Once the decision has been made to explore prototype design, there are two approaches to implementing it in your district. The first is to have the school designed from scratch according to your educational philosophy and foreseeable needs, and then to apply that design (or a variation of it) to the rest of your new schools. The second method is to purchase a prototype design "off the shelf" from a selection of tested school designs (check out www.schoolclearinghouse.org for examples). Once you have decided which route to go, site adaption becomes the major concern.

"The risk is always the site," says Lewis, who recommends site feasibility studies to figure out the best placement of the prototype. "Land is the big caveat," agrees French. "Work very closely with your architect or land planner to make sure a prototype fits well on that piece of property; if it doesn't, you're not going to save any money on fees because it's going to have to be redesigned."

Hughes adds that the design of the school has to be flexible enough to adapt to the site: "The site's not going to adapt to the building. There are long, skinny sites; long, fat sites; and sloping sites. [The school] has to have some inherent flexibility in it to be able to accommodate the different sites because, unfortunately, you don't always get the best piece of land."

The other major challenge with prototype design schools is the rate at which they become obsolete or ineffective. "There is a shelf life for prototypes," says French. With rapidly changing technology, security, and teaching methodologies, the design will eventually need to be changed. "If districts are trying to be as progressive as they possibly can in school design and forward thinking, they need to go back and do checks and balances to see, ‘Have we changed our delivery method in the way we're teaching our kids? And, should we look at possibly tweaking our prototype?' Because, if you're just going to keep laying buildings out there and not evaluating them, I'm not sure you're doing the right thing," says French.

Tweaking the design of the prototype as you go is a best practice that will eliminate problems down the road. Facility managers and school officials should gather input from teachers and students on how the building suits them and meets their needs. FMs should also make sure the building systems are up to date and will work in the long run. "After the building's built, get feedback from the building and grounds workers," says Lewis. These experts can point out practical, operational elements that should be improved on the next go-round.

The Qualities of Successful Prototypes

A good prototype will be extremely flexible and allow for easy changes and adjustments down the road. "We have one school district where we did 14 prototype elementary schools," says Taniguchi. "They were growing so fast that, the year immediately after we built them, we added on to them." Lewis remarks that the design was so flexible that "it could immediately take a 10-classroom addition." Taniguchi and Lewis recommend leaving corridors open-ended so that they can be easily extended, and they warn against burying rooms like cafeterias or gyms that might need to be expanded with growth.

Flexibility is also important as modes of teaching and learning progress. "Small Learning Communities (SLCs) are a big thing in high school design right now," says French, "so, in some ways, schools aren't having as many walls as they used to." More collaborative learning environments require abundant open space and more impromptu meeting spaces than the traditional classroom design. As pedagogy changes, the space must be able to keep up.

Flexible design makes it easier to adapt to specific sites, and it also lends itself to sustainability. "We have to understand that economic buildings have to be high-performance buildings," says Hughes. "We have an obligation to design the kinds of buildings that [are] appropriate to the world we're living in today, and that we anticipate for tomorrow."

Green-building principles (like those outlined by the USGBC's LEED programs) have been proven to save money over time, and are better for the environment. As long as you're building prototypes, why not perpetuate a design that is energy efficient and provides better air quality for students? Taniguchi and Lewis suggest establishing a list of sustainable goals for your district, which could include good indoor air quality, plenty of daylighting, and a reduced amount of impervious pavement outside the building. Hughes knows of one prototype that "uses 50-percent less energy than the typical, code-compliant ASHRAE 90.1 building out there today. It has the potential to generate twice as much electricity as it uses. So, don't write off prototype because it's repetitive and economic. [Prototype schools] can be the most high-performing buildings that we see today."

Jenna M. Aker ([email protected]) is associate editor at Buildings magazine.