By Helmut Kientz

Found primarily in commercial and institutional design, curtainwall systems serve as a design element that can protect building occupants from the extremes in weather while moderating the effects of thermal expansion and contraction, building movement, and more.

First used in the early 20th century, curtainwall construction is not new. The original curtainwall system featured infill material made of metal; the advent of the glass-float process in the 1950s, and development of new thermal and construction technologies in subsequent decades, have led to the escalating use of the curtainwall systems used in design today. Now, in addition to metal, infill materials can be made of monolithic or insulating glass, stone veneer panels, louvers, and even operable or fixed windows and vents.

Although the infill material comprises most of the curtainwall system, it is helpful to understand the types of curtainwall systems available, as well as some points to consider when designing curtainwall systems.

Types of Curtainwall Systems

There are five curtainwall types that are in use today:

- Stick System (Fig. A). In the stick system, mullions (sticks) are fabricated in the shop and installed and glazed in the field. Sticks are placed between floors vertically to support individual components, such as horizontal mullions, glazing, and spandrels. Loads are transferred through connections at floors or columns.

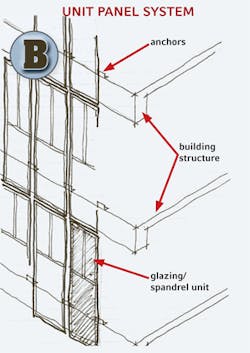

- Unit Panel System (Fig. B). For large or labor-intensive projects, unit panel systems may be a cost-effective alternative to the stick system. In the unit panel system, panels are fabricated and assembled at the shop, and may be glazed there as well. The panels are then taken to the field, where they are attached to a building structure.

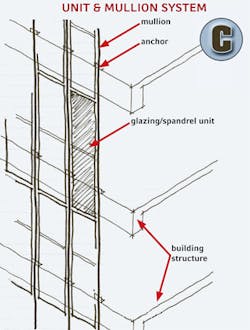

- Unit and Mullion System (Fig. C). Similar to the stick system, mullions are the first tube to be installed in the unit and mullion system. Spandrel and glazing, however, are inserted into the stick system as a complete unit.

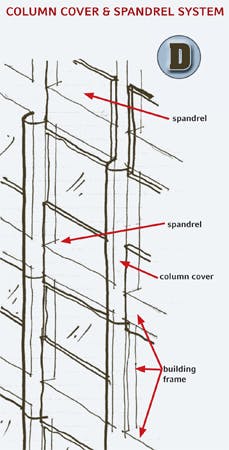

- Column Cover and Spandrel System (Fig. D). While column cover and spandrel systems are similar to unit and mullion systems, they differ in that the building frame is emphasized with column covers, which act as sticks.

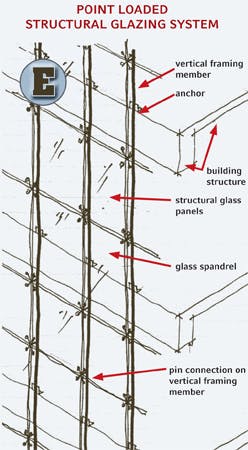

- Point Loaded Structural Glazing System (Fig. E). In this system, the vertical framing member can be comprised of stick, cable, or another custom structure behind the glass. Glass is supported by a system of four-point brackets, and joints are sealed with silicone.

Issues to Consider with Curtainwall Systems

Like any building systems, curtainwall presents several issues that must be considered during design and construction. In addition to air infiltration and deflection, non-deflection-related stress and thermal conductivity loads are, perhaps, the top issues to consider. Because curtainwalls are designed to be non-load bearing, any loads placed on the curtainwall—such as those from the curtainwall elements (e.g. mullions, infill, etc.), weather (e.g. wind and snow), seismic and blast forces, and thermal—must be transferred back to the structure itself.

Fire safety is another area of consideration. Because gaps between floors do little to impede fire and smoke, fire safing and smoke seals should be located between floors to maximize protection. In addition, tempered knockout panels, designed to fracture and provide access during a fire, should be included to reduce safety concerns.

Finally, note that curtainwall systems typically cost more than standard window systems. These costs must be reviewed in conjunction with the need to address special design considerations, such as support framing, glazing types, interior vs. exterior systems, shading devices, applied finishes, special infill materials, etc.

An Ounce of Prevention

Beyond these issues, a variety of factors can influence the performance of a curtainwall system. Air and water infiltration, the quality of materials and installation, and other issues can all lead to curtainwall failure.

To maintain the life and protection of the curtainwall system, periodic checks of items, such as gaskets, seals, system joints, and the thermal-insulation capabilities of vision and insulating panels, should be conducted, and aluminum frames should be cleaned. Furthermore, perimeter sealants, typically designed to have a service life of 10 to 15 years, should be carefully removed or replaced at the end of their life.

Helmut Kientz is senior architect, design and illustration, at Cincinnati-based Hixson.