By Simon Turner and David Handley

In July 1976 in Philadelphia, an outbreak of pneumonia affected 221 people, killing 34. Many were members of the American Legion attending a convention at The Bellevue-Stratford Hotel.

The causative organism, Legionella pneumophila, is commonly distributed in nature and, although positively identified and named only several months after the outbreak of the illness that gave the disease its name (Legionnaires' disease), it has probably been causing infections in humans for hundreds of years - and continues to do so, though the source of an individual infection is commonly obscured. A potential scenario might be an elderly tourist who takes a shower in a hotel and heads home, falling ill about 10 days later and dying of what is known in medical circles as "community-acquired pneumonia" (CAP). But, no one relates the illness to a shower in a distant city's hotel.

Legionella infection is caused by the inhalation of water aerosols containing the bacteria. The numbers of organisms required to induce infection is not known, but varies according to age, general health, and other predisposing factors. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports between 8,000 and 18,000 cases of Legionnaires' disease annually in the United States, but it also estimates that more than 90 percent of cases go unreported. Though it is possible that healthy people can contract this illness, people with compromised immune systems, respiratory illnesses, and cancer are much more likely to become infected. It is estimated that 10 to 20 percent of those infected die, but in individuals with compromised immune systems, the fatality rate is likely to be much higher.

Where You Can Find Legionella

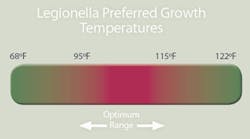

Legionella species occur naturally in soil, rivers, and lakes, and have the ability to successfully colonize manmade water-handling and storage systems, which often provide ideal nutrition and temperature conditions. Legionella bacteria have an optimum growth temperature of between 95 and 115 degrees F., an optimum pH of between 5.0 and 8.5, and often flourish inside scale and sediment (where they are protected from hot water and chemical disinfectants).

The potential for legionella to become hazardous to large numbers of people is greatly enhanced by conventional water and air-conditioning engineering methods used in recirculating cooling towers, air-conditioning chill coils and humidifiers, water storage and distribution systems, and aquatic systems (such as whirlpool spa baths); however, the potential for your building's hot and cold domestic water systems to harbor legionella should not be underestimated.

While many of the well-publicized, mass cases of Legionnaires' disease have had their origins in cooling towers, it is thought that the vast majority of sporadic cases are coming from domestic building water systems, especially where a spray may be generated from items such as showers, spray faucets, sidewalk or salad bar misters, or ornamental fountains. The bacteria like to lodge where biofilm, scale, and sediment accumulate.

How You Can Prevent Legionella

Good maintenance of cooling towers and plumbing systems is imperative to keep legionella at bay, but no water treatment and maintenance system is guaranteed to fully and permanently eradicate the organism. A large water service industry has developed to maintain cooling towers; generally, less attention is applied to domestic plumbing systems. Moreover, continuous chlorination, the method used for most cooling towers in the United States, is not an option for potable water systems. A good reference for water system maintenance is ASHRAE's Guideline 12-2000: Minimizing the Risk of Legionellosis Associated with Building Water Systems, which can be downloaded online.

For every water system, there should be a risk assessment, followed by the development of standard operating procedures and a written maintenance plan.

For cooling towers, the Rockville, MD-based Association of Water Technologies recommends the following practices for prevention:

- Prevention programs for corrosion, scale, and deposits.

- Dispersant, biodispersant, and antifoulant programs.

- Biocide programs.

- Mist-elimination technologies.

- Twice-yearly washout and cleaning programs, including oxidizing disinfections.

For domestic plumbing systems, the design should be reviewed; dead legs, storage tanks, and low-flow conditions should be identified. Any water systems set up to allow for low flow or stagnation should be amended to allow for recirculation. The systems should be specified to store the hot water at 140 degrees F. and deliver it at a minimum of 122 degrees F. at the point of use. This should be achievable within 1 minute of running the outlet. Clearly, this will require effective circulation of the system and good insulation of the hot water supply lines. There is always the concern about scalding - scald-protection equipment (such as thermostatic mixing valves) should be specified. Organics leaching from rubber or silicone gaskets are favorite sources for nutrients for legionella, and designs of hot water systems should eliminate these components where possible. Water pumps in high-rise buildings are often set up with a rooftop-mounted header/expansion tank. The tank can cook in the sun and be an obvious source of legionella, "seeding" building water systems with bacteria. To prevent stagnation, water pumps should run continuously and not be included in energy-conservation programs.

There are pros and cons of using point-of-use water heaters - they can minimize stagnation in rarely used lines, but they can also be a frequent source of leaks and floods. Point-of-use heaters with small holding tanks are a common breeding ground for legionella.

Water system temperatures should be regularly assessed. Hot water tanks should be regularly flushed and cleaned with a suitable disinfectant, and should be fully flushed out before being placed back in service.

How You Can Treat Legionella

OSHA publishes guidelines and recommendations for the control of legionella with a two-level approach to diagnosing the building water system. After a reported case of Legionnaires' disease, this manual should be consulted for treatment and testing procedures, and monitoring actions.

The Level One investigation (initiated when there's probable basis for suspecting that water sources are contaminated with legionella, or when there is information that one case of Legionnaires' disease may exist) consists of an overview of the building water systems via a walkthrough, an identification of components that may present risk, and any recent changes in the system. Water temperatures and the condition of the systems should both be assessed. After any control changes are made, testing of the water system for legionella is then advised. The table on page 50 shows the action levels recommended for different water sources. Interpretation of positive results should take into account the serogroup identified (there are 30-plus species of legionella and at least 14 serogroups of Legionella pneumophila, but the Pontiac subtype - serogroup one - is responsible for more than 90 percent of known infections); if conditions allow the presence of serotypes not commonly associated with illness, then conditions could be ripe for more pathogenic serogroups to grow.

The single isolation of these bacteria from a water system doesn't mean that the disease will necessarily manifest itself, but if the contaminated water becomes an aerosol, the risk of human infection is greatly increased. Thus, if manmade water systems produce jets, sprays, or mists (as with cooling towers, showers, and some types of humidifiers), it's important to minimize the chances of legionella colonizing the water reservoirs, storage tanks, and other aquatic systems serving them.

If more than two cases of Legionnaires' disease have been traced to a particular building, this is considered an "outbreak" and the Level One procedures should be supplemented by medical surveillance of building occupants out on sick leave, employee-awareness training, a historical assessment of sick-leave records, and water sampling. Medically, Legionnaires' disease is a reportable condition in most states, but this does not necessarily mean that the building owner is required to report conditions or results of the control program in the building. Consult local regulations on this matter.

OSHA Action Levels for Legionella Levels in Building Water SystemsColony-Forming Units (CFUs) of Legionella Per Milliliter

Action

Cooling tower

Domestic water

Humidifier

1

100

10

1

2

1,000

100

10

To treat legionella in cooling towers: If remedial control measures are required, your water-treatment company should provide you with a plan that is consistent with the OSHA technical manual. OSHA refers to the Wisconsin Protocol for the cleaning and treatment of contaminated cooling towers, a well-established and defensible procedure. There are a variety of biocidal treatments beyond conventional chlorination to consider (bromine, chlorine dioxide, and a wide range of non-oxidizing biocides, etc.). Each has its pros and cons. There is a sound technical basis to the use of alternating treatments that prevent the development of resistant strains of bacteria in the system.

To treat legionella in domestic plumbing systems: Treatment options for your hot water systems start with cleaning of components and pasteurization, which consists of raising the temperature at each supply outlet to more than 158 degrees F. for 24 hours, followed by flushing each outlet for 20 minutes. There is an obvious concern for scalding during this process, so building occupants should be notified.

Cold water line infestation with legionella is less likely and may occur as a result of cross contamination with the hot water system. Backflow preventers can help with this problem. One option for solving cold water line contamination is to chlorinate the cold water system. Free chlorine levels of 20 to 50 ppm should be maintained for 1 hour at 50 ppm, or 2 hours at 20 ppm. In most large buildings, this is complicated by the presence of ice machines and other fittings, each of which requires specific and focused service work to clean and ensure that residual chlorine is removed.

Fire-sprinkler systems are, by definition, "dead legs." In the event of a fire, the direct risk from the fire is the primary concern; legionella is a minor risk by comparison. If a sprinkler leaks or is accidentally activated, expect the water showering into the building to be potentially contaminated with legionella; however, the disease vector is via aspiration, not skin contact. Unless building occupants are caught directly in the spray, floodwaters are less likely to cause Legionnaires' disease than other problems, such as mold and property damage. Care should be taken, however, to ensure that a safe method is devised for testing of these types of systems, because the highest risk is to the maintenance personnel doing such testing.

Cooling towers have long been known as sources for legionella growth; as a result, engineering departments go to great lengths to manage these water systems safely, with water-treatment programs designed specifically to ensure that they are hostile to the growth of legionella, including chemical treatment with chlorination or other compounds. Less well known is the ability of legionella to lodge in domestic water supplies where chlorine concentrations will be lower and water temperatures are kept at levels that don't scald building users. It may come as a surprise how frequently this organism is growing in a building's domestic water supplies.

In many parts of the world, risk assessment and monitoring of commercial building water systems are more highly regulated and intensive than they are in the United States. This may change as science allows more definitive tracing of sick individuals to specific buildings.

Building owners, stung in the past by asbestos and mold liability, should be aware of the risks associated with legionella. With any indoor environmental issue, however, they can take proactive steps to protect their interests.

Simon Turner is president at Irvine, CA-based Healthy Buildings Intl. Inc. (www.hbiamerica.com). David Handley is managing director at Healthy Buildings Intl. Ltd., United Kingdom (www.hbi.co.uk).