Legionella bacteria, which can cause Legionnaires’ disease, are common in warm, freshwater environments like lakes and streams. They can also grow and thrive in building systems, particularly hot water systems. Such contamination can occur during water’s transit from a centralized treatment facility through distribution pipe networks to various facilities and in-building (“premise”) plumbing systems.

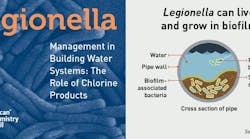

Legionella bacteria are often found in biofilms, slimy coatings of microbial growth on pipe walls, and their control is a key challenge in any building water system. Biofilms provide a hospitable environment in which Legionella and other microorganisms can grow, shielded from contact with disinfectants.

Buildings that have been idle for an extended period of time, for any reason, are more susceptible to Legionella growth and risk as critical residual disinfectant levels drop or disappear entirely in stagnant water. This is of particular public health concern during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in many fully or partially closed buildings.

Also, many hot water tanks are deliberately set at lower temperatures year-round to conserve energy, potentially resulting in the unintended consequence of providing favorable Legionella growth conditions.

People can be exposed to Legionella when they inhale aerosols or mists from household plumbing, cooling towers, showers, decorative pools and waterfalls, as well as hot tubs contaminated with the bacteria. Inhaling water droplets and mists containing Legionella can lead to Legionnaires’ disease, a severe and sometimes deadly form of pneumonia. In healthy individuals, inhaling Legionella is more likely to result in Pontiac fever, a milder, flu-like illness.

Individuals and groups most at risk for Legionnaires’ disease include occupants of healthcare facilities, smokers, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals.

To help prevent Legionella outbreaks, the American Chemistry Council (ACC) has sponsored a free, downloadable booklet, “Legionella Management in Building Water Systems: The Role of Chlorine Products.”

Written by noted Legionella expert Dr. Joseph Cotruvo, the 33-page booklet has five chapters. It provides an overview and summary of information to help building managers, engineers, and owners of at-risk facilities better understand and manage the risks of Legionella in premise plumbing. It advocates for a practical and proactive approach to mitigate Legionella-related risks, focusing on real-world examples and currently available methods for assessment, mitigation, and prevention.

The booklet also provides citations of key literature and guidance for those interested in exploring the relevant issues and technologies in greater detail before assessment or mitigation decisions are made and contractors engaged.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has identified Legionella as the most common cause of reported drinking water-associated waterborne disease outbreaks in recent years, and the only type of outbreak that resulted in reported deaths. Thousands of water-related cases and hundreds of deaths from inhalation of Legionella have been reported worldwide.

Contracting Legionnaires’ disease, or the more common but far less severe Pontiac fever, is a risk in any part of the world, but it is likely to be more common in the developed world given the extent and density of indoor plumbing, cooling towers, hot tubs and spas, and elevated concentrations of high-risk patients in hospitals and nursing homes.

Because the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency does not regulate Legionella in building water systems, policies and procedures affecting location-specific mitigation measures are determined by individual states and local governments. A growing number of reports and guidelines on Legionella prevention and mitigation technologies are available, but can be difficult to interpret and apply at specific buildings.

The ACC-sponsored booklet on Legionella management compiles much of this information on prevention and mitigation of Legionella risks into one guide. The principal disinfection technologies for building water systems reviewed in the booklet are free chlorine, chloramine (monochloramine, also called “combined chlorine”), chlorine dioxide, and copper-silver ionization.

The booklet also addresses flushing, shock heat, and shock chlorination measures. It emphasizes that any prevention and mitigation of Legionella risk in building water systems should be associated with the development, application, and periodic revision of a site-specific comprehensive Water Safety Plan or the equivalent.

To help avoid an increase in Legionella outbreaks as Americans return to work and school, the new ACC-sponsored booklet can help promote the safety of building water systems, whether after prolonged shutdown or during normal operations.

Download a free copy of the booklet at legionellabooklet.com.

About the Author: Mark Gibson; Director, Chlorine Issues; American Chemistry Council

*This is sponsored content, provided by American Chemistry Council.