The Flight 93 National Memorial Honors the Heroes of 9/11 and Helps Heal the Land

For those of us who lived through the Sept. 11 terror attacks in 2001, it’s difficult to process how 20 years have passed since the searing images of passenger airplanes striking the Twin Towers in New York City were etched permanently into our minds. What no one witnessed at the time but discovered later was an act of heroism by 40 passengers and crew who prevented another plane from crashing into our nation’s capital and who lost their lives in the process.

The Flight 93 National Memorial, built at the site of the crash in rural Pennsylvania, poignantly retells the story of that fateful morning through the language of design, transforming a former reclaimed coal strip mine into a memorial landscape of symbolic and environmental healing.

This is a project nearly two decades in the making that embodies the spirit of the memorial’s mission statement preamble: “A common field one day. A field of honor forever.”

The Morning That Inspired a Monument

The morning of Sept. 11, United Airlines Flight 93 departed Newark International Airport for San Francisco after a delayed departure, carrying 33 passengers, seven crew members and four hijackers. Approximately 45 minutes into the flight, the plane changed course near Cleveland, Ohio, and was redirected southeast toward Washington, D.C. After the passengers and crew members overtook the hijackers, Flight 93 crashed a few minutes after 10 a.m. in a field near the town of Shanksville in Somerset County, Pennsylvania, leaving no survivors.

The Flight 93 National Memorial is a 2,200-acre national park site designed by architect Paul Murdoch and his team at Los Angeles-based Paul Murdoch Architects in collaboration with Virginia-based landscape architecture firm Nelson Byrd Woltz that commemorates the lives and actions of the heroic passengers and crew. The Flight 93 Advisory Commission, a federally appointed body charged with making recommendations for the planning, design, construction and management of the national memorial, selected Murdoch’s design proposal from among 1,100 entries.

“We looked at what was unfolding on 9/11 from our distant computer screens in Los Angeles that day and felt pretty helpless watching this. It was just the most awful day,” Murdoch recalled. “I said that day, ‘We need to do something here.’”

As architects and designers, Murdoch felt strongly about participating by commemorating the heroic efforts of the passengers, crew members and first responders although he didn’t know how at the time. When he saw an advertisement for the competition to design the Flight 93 Memorial, “We jumped at the chance,” he said.

The first phase of the project, dedicated in 2011, included the entry road, re-grading of the large Field of Honor and the memorial features adjacent to the crash site. The memorial landscape moves visitors through a composition of open spaces defined by site walls, plantings, walkways and courts, gateways, and building elements.

At the heart of the memorial landscape is a large, bowl-shaped field where the mine was previously located now framed with a distinct, formal edge that delineates the site as a “Field of Honor.”

“We had this idea that we would frame this field, the edge of this field in this very large-scaled embrace so that it’s a nationally scaled embrace of this place,” Murdoch said. “That was our expression of that ‘Field of Honor’” that’s referenced in the preamble.

Along the perimeter of the field, the memorial’s features include:

- A visitor center, which was dedicated in 2015 and is located between two ascending concrete memorial walls that are aligned with the flight path

- 40 memorial groves with a Red Maple allée

- The Wall of Names and Memorial Plaza, the Arrival Court and Gateway, and the restored wetlands

- The Sacred Ground

- The Western Overlook

When visitors arrive at the memorial along the edge of the field, the elevation is 200 feet higher than the crash site beyond, which was an important element of the design because it denotes the spot where Flight 93 flew directly overhead and provides a sweeping view of the entire site, Murdoch explained.

“There’s a tall, narrow opening in that pair of walls that the flight path walkway takes visitors through to an overlook where that pathway stops,” he said. “At the guardrail of that overlook is the preamble to the mission statement, and when you come through the second wall—that tall narrow opening—that’s when the field just opens up. It’s a vast expanse. It’s a very dramatic point. And then from that overlook, you get your first view straight down the hill to the crash site.”

Healing the Land

The plane crashed at the edge of an open field in front of a grove of hemlock trees, many of which were scorched in the inferno. It serves as the backdrop to the site and the focal point for the entire memorial experience.

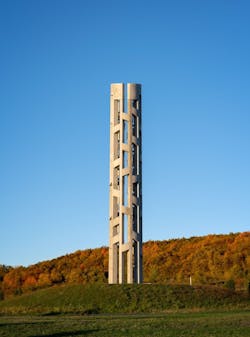

The distinct structure of the trees, with their straight, tall trunks and alternating angled branches, is the inspiration for the design motif expressed in materials throughout the memorial, including concrete paving, the visitor center ceiling and glasswork, and in the structural design of the Tower of Voices at the entrance to the park, among others.

“The hemlock grove has fairly shallow roots, but they form a network of roots together—the whole grove—and it became a very powerful metaphor for what the 40 people on the plane did,” Murdoch observed. “So, while the visitors can’t go into the hemlock grove because it’s at the sacred ground of the crash site, we use the hemlocks as inspiration in the materials throughout the whole memorial.”

Every aspect of the landscape works to repair the damaged land and water—from the restoration of meadows and wetlands to the remediation of soil and the planting of diverse native tree species. The complexion of the memorial landscape is intended to change over time and seasons.

Daylight is used in the visitor center to connect visitors to the natural and commemorative landscape, so the story told in the displays always has a direct connection with the site. Cast-in-place concrete walls and black-stained precast panels at the interior feature a finish made from 150-year-old recycled Pennsylvania barn timbers. This creates a symbolic connection with the hemlock grove down the hill that absorbed the impact at the crash site.

[Related: One World Trade Center Officially U.S.’s Tallest Building]

Murdoch noted that the visitor center is not recognizable as a building but rather as part of the site work. “It was very important that we have it there at that location, right at the intersection where the flight went overhead at the edge of the bowl, so that the visitor center was not just [about] the exhibits, but it was also viewing firsthand the site itself and that the spatial continuity through the visitors center was all part of the landscape,” he said.

In order to accomplish that goal, Murdoch and the design team rejected the idea of creating a “black box” type exhibit hall and opted for ample daylight and views of the site within the space. However, archival material in the exhibits required low light levels, requiring sophisticated daylight studies with a lighting engineer and lighting designer, he noted.

Eight different glass types respond to the various exposures to enhance building performance while mitigating negative effects on the exhibits. This careful location of building apertures and high-performance glazing of various types allows the interior to be visually connected with the memorial landscape and its many moods, promoting personal reflection.

Recycled aluminum radiant ceiling panels, a variety of high-performance glazing types and hemlock wall panels all contribute to the story and sustainability of the project.

[Related: How This Brownfield Transformed into an Aspirational School Campus]

A Place of Remembrance and Healing

Upon entering the park, visitors first see the Tower of Voices that marks the gateway to the memorial site and commemorates the 40 passengers and crew as a living memorial in sound to remember their ongoing voices.

Murdoch said the tower symbolizes a “confluence of what the site offered” and what happened that day. “In this case, the last memory of a lot of people on the plane were through their voices on phone calls, so that’s where the inspiration came for the Tower of Voices,” he recalled.

It was conceived as a tower because the design team wanted a welcoming landmark at the entrance to the site. The tower—believed to be the largest wind-driven chime in the world—was the final piece of the memorial to be completed, which was dedicated in 2018. The wind-activated, 93-foot-tall Tower of Voices required an unusual combination of consultants, including a musician, chimes artist, acoustical engineer, wind consultants, sail designer and detailed design process.

The overall design approach of the memorial is to encourage visitors to experience the natural, historic and commemorative places throughout the park by walking through a spatial sequence of trails and designed places. The active engagement of walking in this setting allows each person the time and space to come to terms with the events that occurred on 9/11 and to reflect on the impact of those actions. Besides the health benefits of walking in a park, the exposure to emotional and spiritual healing is the main wellness goal, achieved through an evolving landscape that is designed to heal over time.

“We’ve tried to create a place where people can heal while we’re also trying to heal the land,” Murdoch said.

Twenty years later, the memorial design expresses the convergence of the land’s beauty and power with the strength and sacrifice of heroic, personal action on Sept. 11 that gives the memorial site its unique sanctity.

“It’s an extraordinary thing what these 40 people did on this plane, and this memorial and this park is set aside to commemorate them and their actions, and that there is a sustained relevance throughout our continuing history means to me that it’s an important place for us and for people to visit,” Murdoch concluded.

Read next: Can Greener Hospitals Save People and the Planet?