For the past 5 decades, the commercial roofing industry has been preoccupied with the membrane components of the roof. The polymeric alphabet soup of EPDM, PVC, SPF, TPO, KEE, CPE, CSPE, MB (APP), and MB (SBS) is still a primary focus, along with the older asphalt and coal-tar pitch membranes.

We also have a variety of attachment methods: fully adhered, mechanically attached, ballasted roofs, cold process, vacuum, and self-adhered membranes. While the above systems deserve recognition, much of their success can be attributed to the various fastening devices that have evolved. Fasteners fasten a roofing component to the roof deck, and the type of deck dictates the dominant features of the fasteners.

This column will look at fasteners from a historical perspective, since many building owners and managers have to deal with repairing or reroofing older properties at some point; it can be important to recognize what the existing roof deck is and how the roof is attached to it.

Gypsum Decking

During WWII, steel was in short supply. Gypsum decking was readily available. It was fireproof, which was important in case the United States was attacked. The gypsum slurry was poured over form boards and usually wire-reinforced for added strength. Since gypsum had a potential for developing shrinkage cracks, the bituminous roofing industry used nailed base sheets to bridge the developing cracks and to serve as the foundation of the BUR roof system. One of the standard nails used was a cut nail, which gained withdrawal strength by rusting. The nail was driven through a thin tin cap. Somewhat later, a conical nail was developed which expanded when driven into the gypsum, forming a wedge to resist pullout. This was more reliable than waiting for rust to develop.

How would you reroof an old gypsum deck today? First of all, the new roof design would undoubtedly require roof insulation.

Neither the cut nail nor conical fastener would be long enough to reach through insulation board into the gypsum decking. A Tube-loc® nail would be one choice (Figure 1). This is a two-piece fastener in which the tube is first driven, followed by a nail. The bottom of the tube is pinched, causing the nail to deform into a hook, providing excellent withdrawal resistance. Tube-loc nails are long enough to drive through several inches of roof insulation. Another choice would be to carefully evaluate and repair damaged decking, following the instructions of the National Roof Deck Contractors Association (NRDCA). If the rest of the decking is hard and dry, all the shrinkage cracking that will occur has probably happened. Since gypsum decking is non-combustible, installers could solidly mop new roof insulation directly to it, followed by a fully adhered BUR, modified-bituminous roof, or even single-ply. A ballasted roof system is not recommended, as the decking and structure may not be strong enough to support the dead load.

Wood Decking

Another common deck on 1940 structures was heavy timber construction. Again, no thermal insulation was the rule, and a nailed base sheet was installed using nails and tin caps. Later on, nails with an integral head were used. While heavy timber is combustible, it is very slow burning and there are very few fire concerns with its use. Installers don't solidly mop to timber decks due to concerns about bitumen dripping into the building or tensile-induced splits as the wood ages and shrinks. Nails had barbs or annular rings to increase withdrawal resistance (Figure 2). Today, insulation laid dry over a solid wood deck might be used, followed by various screws and stress plates. A system using staples driven through reinforced tape is still used, generally on newer plywood and OSB decking where no roof insulation is to be used. On the mild West Coast, fiber glass batts might be installed between the rafters below the OSB decking. Wood-decked buildings typically achieve their fire ratings from installed sprinklers rather than by using Class 1 roofs.

Lightweight Insulating Concrete

While structural concrete is strong and hard, there are versions called structural lightweight concrete with a dry density of around 105 pcf, compared to standard concrete at 150 pcf. Both products are frequently roofed using hot asphalt or various single-ply adhesives. However, for some single-ply systems, mechanical fasteners are used. This generally requires a two-step process, first to pre-drill the roof deck, followed by a threaded fastener or “spike.” Neither structural nor structural lightweight concrete has much thermal resistance, so installers would mop the insulation or fasten through it into the concrete decking.

There is a third version of concrete called lightweight insulating concrete. The dry density is down around 30 pcf; it achieves this low weight by the use of expanded aggregates such as perlite and vermiculite (air-entraining agents), or both. While this product has somewhat better insulating qualities, for new construction, it invariably incorporates expanded polystyrene foam for today's necessary high R-values. These decks are poured over a form deck, commonly 26-gauge slotted steel, but also have been poured over structural concrete by using less water and a fill richer in Portland cement (called the non-ventilating substrate mixture).

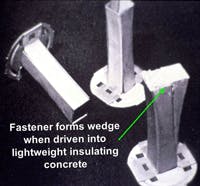

Because lightweight insulating concrete decks contain high water content even after years of service, the roofing industry does not attempt to solidly adhere a roof membrane to it, but instead uses special fasteners designed for this low-strength fill. Figure 3 illustrates a hinged fastener that cuts through the base sheet and forms a wedge in the lightweight concrete. Pull-out strengths for these decks are quite low, typically about 40 pounds withdrawal, compared to several hundred pounds per fastener in steel, wood, and concrete. Fastener spacing density is increased to compensate for the low pull-out.

Steel Roof Decks

Because steel decks have flutes, they require a bridging layer, which is typically roof insulation (although various leveling boards are also used such as gypsum board).

Until 1953, steel decks were considered non-combustible, and roof insulation was generally attached by mopping directly to the steel. However, a major interior fire that year revealed that, in the case of an under-deck fire, the fuel content of the asphalt and vapor retarders could vaporize and contribute to widespread fire loss. After 1953, asphalt and other combustibles were severely restricted. Less-combustible roof insulations, such as perlite and glass fiber, could meet FM requirements with limited quantities of bitumen, generally applied in ribbons directly to the deck. Non-bituminous vapor retarders, such as PVC, glued to the deck with polymeric adhesives were introduced as well. However, attachment of these products was not all it was hoped for, partially due to misapplication of the adhesives. By the 1960s, it was common practice to supplement the adhesives with perimeter fastening, using either of two piercing fasteners: the Riv-Nail® or the Lexsuco Clip™. Gradually, more roofing jobs incorporated mechanical fasteners throughout the roof area.

By 1986, FM Global elected to prohibit not only hot-asphalt application, but cold adhesives as well. This gave great impetus to the development of all sorts of mechanical devices, especially self-drilling and self-threading screws combined with various stress plates.

As the single-ply industry gradually captured more and more of the roofing market, innovations included placing fasteners only in the seams of the single-ply membranes. To be cost effective, more sophisticated fasteners and stress plates were introduced, as well as “fixation bars” that were fastened through the membrane and covered with a membrane batten, either welded or adhered.

Another issue that FM recognized was that fasteners could corrode, losing much or all their wind resistance as they rusted out. This led to the introduction of the Kesternich sulfur-dioxide test (ASTM D 6294). Virtually all fasteners now meet FM corrosion resistance requirements by using polymeric or metallic coatings.

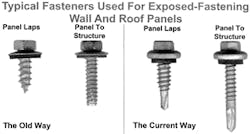

Fasteners for the metal roofing industry evolved as well. An excellent overview of metal roof fastener technology by Bob Fittro, editor-in-chief of Metal Architecture magazine, was published in the December 2006 issue. Figure 4 illustrates the past and current practice with metal roofing fasteners, illustrating the use of EPDM washers for their superior weathering resistance and self-drilling and tapping fasteners for faster installation and increased corrosion resistance.

|

Figure 4: SOURCE: Photo by Triangle Fastener Corp., reprinted with permission from the December 2006 issue of Metal Architecture magazine

|

|

| (left)The invention of the bonded sealing washer by Fabco® allowed the use of self-tapping fasteners for attaching metal panels. These fasteners allowed the installer to secure the panel from one side, eliminating the use of bolts and nuts. Panel and structure had to be pre-drilled and self-tapping screws could then be installed. The popular sealing washer material at that time was neoprene. | (right)The most common fasteners used today are self-drilling types that eliminate the need for pre-drilling. They are available with zinc or stainless heads, can be made from stainless steel (304 and 410), and can be assembled with cut-tubular or bonded sealing washers. The sealing washer material used today is EPDM for its excellent weathering characteristics. |

Precautions When Using Long Fasteners

It may appear cost effective to use thick single layers of roof insulation when constructing low-slope roof systems. However, thick layers, especially of isoboards will tend to thermally warp. NRCA recommends that, when more than 2 inches of isoboard is used, multiple layers of boards (with vertical joints offset) be considered. Another consideration is thermal loss by conduction through the fasteners. Figure 5 illustrates melted snow at each fastener location. The old adage that says “nail one layer, then adhere one” avoids this problem.

Resources on roofing fasteners:

National Roofing Contractors Association www.nrca.net

National Roof Deck Contractors Association www.nrdca.org

Metal Architecture magazine www.metalarchitecture.com

Single Ply Roofing Industry www.spri.org