In a multistory building, elevators are one of the most common ways to provide access for tenants and visitors—and they’re often one of the first accessibility elements added to a new building.

In new and existing buildings, elevators must conform to the guidelines set forth by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which was signed into law in 1990 and ensures that people with disabilities receive reasonable accommodations in order to participate in society—including access to public and commercial buildings.

Your elevators might be exempt from ADA compliance if your building has fewer than three stories or fewer than 3,000 square feet per floor. However, the exemption doesn’t apply if your building is a:

- Professional office of a health care provider

- Public transit station

- Airport passenger terminal

- Shopping center or mall

Principal consultant of ADA Consulting of Indiana David Meihls says most elevators today are manufactured to be ADA compliant. But it's a smart business move to know the ADA elevator requirements to provide the best experience for your tenants and their clients—and to avoid the time and expense of remodeling later.

When purchasing an elevator or evaluating an existing installation, review the elevator ADA requirements to ensure your system is compliant.

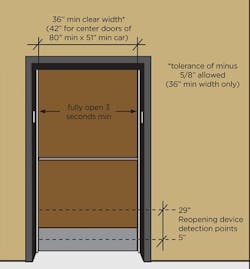

(Diagram courtesy of the United States Access Board)

These requirements state that:

- Elevator must be easily accessible in a public space (instead of, for example, a cramped hallway)

- Doors must remain fully open for at least three seconds

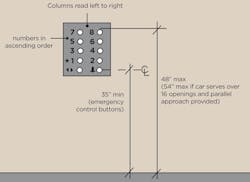

- Call buttons are a minimum of 0.75 inches in diameter

- Button heights must be centered 42 inches from the floor

- Car must be at least 51 inches deep and at least 68 inches wide

- Door width must be at least 36 inches

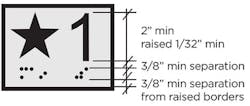

- Braille must be below or next to floor numbers on the control panel

- Automatic verbal announcement of stop or non-verbal audible signal of passed floors and stops must be used

- Two-way communication must be available in elevator cabs that deaf/blind users can use

- Emergency controls must be grouped at the bottom of the elevator control panel and have their centerlines no less than 35 inches above the finish floor

Many of these requirements are standard across all types of elevators—but certain systems can have requirements unique to their technology.

Destination-Oriented Elevators

Destination-oriented elevators group passengers for the same destination to reduce wait and travel times. When using a destination-oriented elevator, an occupant calls an elevator car by first indicating which floor they need, usually on a keypad. Lobby indicators will then tell the occupant which car to use to get to their destination.

[Related: 3 Rising Trends to Watch in Elevator Technology]

The ADA says these types of elevators are held to the same specifications as a traditional passenger elevator—but requirements specific to destination-oriented elevators include:

- Audible and visible differentiation of each elevator in an elevator bank (so occupants easily know which one to use)

- Visual display of each floor at which a car has been programmed to stop

- Automatic verbal announcement of each car stop

Limited Use/Limited Application Elevators

A limited use/limited application elevator (also known as a LULA) is smaller and slower than a traditional passenger elevator you’d find in a large commercial building. LULAs are designed for low occupancy and typically will only take an occupant up one or two stories, says Meihls. They’re often found in churches, schools, libraries and small businesses.

LULAs can also be added as a way to improve accessibility in existing buildings. When you alter, renovate or expand your building, the ADA’s 2010 Standards for Accessible Design (the most recent version) requires the removal of “accessibility barriers in existing places of public accommodation when doing so is readily achievable” to be compliant.

The ADA defines “readily achievable” as “without much difficulty or expense.” But how can you, as a building owner, decide what needs to be done?

“One effective approach is to conduct a ‘self-evaluation’ of the facility to identify existing barriers,” the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) states on the ADA website.

A self-assessment isn’t required by the ADA, says the DOJ, but it’s worth its weight in identifying the most efficient ways to provide access that is required—and in preventing liability. It also serves “as evidence of a good faith effort to comply with the barrier removal requirements of the ADA,” notes the DOJ. An assessment should include individuals with disabilities or the organizations that represent them.

According to the ADA, LULAs are, for the most part, held to the same standards as traditional elevators. But they also operate differently—with smaller car sizes, slower speeds and shorter travel distances.

BUILDINGS Checklist

How to Handle ADA Complaints Exclusive Checklist

Did you know the most crucial steps are the ones you take right away after receiving a complaint? Ignoring the situation could set you up for a lawsuit. Be proactive with this checklist >>

(Un)Common ADA Violations

Although Meihls says he rarely encounters ADA violations when inspecting elevators, it does still happen.

Another violation he often sees is the lack of areas of refuge within a building. Areas of refuge are designated locations in a building, often adjacent to or within a stairway, for occupants to wait during an emergency when evacuation is not safe or possible.

The areas should feature enough space for a wheelchair (30-inches-by-48-inches minimum), and there should be one for every 200 occupants. They should also feature a two-way emergency communication system.

Although this violation doesn’t include elevators directly, these areas are often needed when elevators are not working in the case of an emergency, and therefore not an option for people with disabilities to use to exit the building.

“Often these aren’t included in older facilities,” Meihls says, adding: “We need to have a place for a person with a disability to go to, and first responders should be trained to know where to look for them.”

The International Building Code (IBC) says areas of refuge aren’t required if facilities are equipped throughout with an automated sprinkler system.

BUILDINGS Podcast

Upward Elevator Trends Taking Over the Industry

The elevator industry is going through some exciting innovations, including fitting more elevators into fewer shafts that operate independently from each other. Listen to more >>

Looking Ahead for Code Changes

If you’re unsure about whether or not the elevators in your buildings are up to code, ask your elevator service provider to survey the elevators and submit a list of recommended changes. An elevator or ADA/accessibility consulting group could conduct a similar survey.

At time of publication, Meihls wasn’t aware of any upcoming code changes regarding elevators. He reiterates that when it comes to ADA compliancy, elevators excel.

“It’s an example as to how well they have trained their people throughout their industry,” he says. “In larger commercial jobs, the elevator is rarely a component I have to worry about.”

For general accessibility, the Institute for Human Centered Design has an updated, downloadable ADA checklist for existing facilities to help guide owners in the process of making their facility accessible—and enjoyable—for all.

This article was originally published April 30, 2009 by Leah B. Garris, former managing editor for Buildings. It was updated on November 5, 2019 by Sarah Kloepple, staff writer for Buildings.

Correction: This article previously misattributed the definition of areas of refuge to the 2010 ADA Standards. We regret the error.

More about ADA compliance in your facility: